Understanding the Journey to Doctoral Education: Results from the 2019 FUTURE PhD STUDENT SURVEY

Executive summary

This report presents the key findings from a survey of over 1,000 prospective PhD students, undertaken by FindAUniversity: publishers of FindAPhD and FindAMasters.

It presents the first ever such investigation of the intentions, motivations, information needs and concerns of people actively considering commencing a PhD qualification.

Prospective students are primarily motivated to consider a PhD by interest in their subject, but the opportunity to acquire transferable skills and to qualify for an academic career are also key drivers. Anticipations of workload are generally high, with more than 50% of both full-time and part-time students expecting to work hours equivalent to a full-time job (or greater). Those considering a PhD are also concerned about the impact of doctoral study on their work/life balance and personal wellbeing.

Responses vary across different subject areas, with prospective STEM students generally being more confident of career plans and funding options, whilst prospective Arts & Humanities students are more likely to be undecided.

Brexit is a concern for UK and for EU nationals, with uncertainty persisting despite the extension of UK fee and funding guarantees.

Table of contents

The audience of prospective PhD students is vast: over half a million people visit FindAPhD each month, whilst our specialist PhD recruitment events attract between 400 & 900 potential doctoral students each day.

All of these are people at some stage in the journey towards a PhD, yet much of that journey goes unrecorded and unremarked by the postgraduate education sector as a whole.

Existing data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) reveals the number of people who successfully go on to study or complete a PhD, whilst Advance HE’s annual Postgraduate Research Experience Survey (PRES) measures doctoral students’ feedback and perspectives.

As valuable as they are, both HESA and PRES only consider the situation and experience of current PhD students. The motivations and expectations of prospective students are absent from these datasets, as are those of the people who, for whatever reason, do not complete the journey to PhD study.

This means that both datasets primarily serve as a rear-view mirror for postgraduate recruitment. And the road ahead is changing.

Investment in new UKRI studentships for AI and other priority subject areas, the advent of doctoral student loans and the coming introduction of a new Graduate Route visa all have the potential to significantly increase the attractiveness of PhD study in the UK.

This report seeks to understand the students who will take up these new opportunities and drive future growth in doctoral education. It draws on the unique size and scope of the FindAPhD audience to present the first ever detailed analysis of the motivations, expectations and information needs of prospective PhD students, together with the obstacles they face.

The results should be of interest to a range of professionals working in areas related to postgraduate education. New insights into prospective students' information seeking processes and perceived barriers to study will be particularly useful to postgraduate marketers and recruiters, whilst the information on motivations, expectations and funding attitudes may contribute to conversations around policy and provision for doctoral education.

Dr Mark Bennett, Head of Content, FindAUniversity

Survey design

The survey included a total of 29 multiple choice, Likert scale and free-text questions.

Data was collected during June 2019, using the SurveyMonkey platform. A call for participants was circulated in the FindAPhD newsletter and via our social media channels.

Audience and sample size

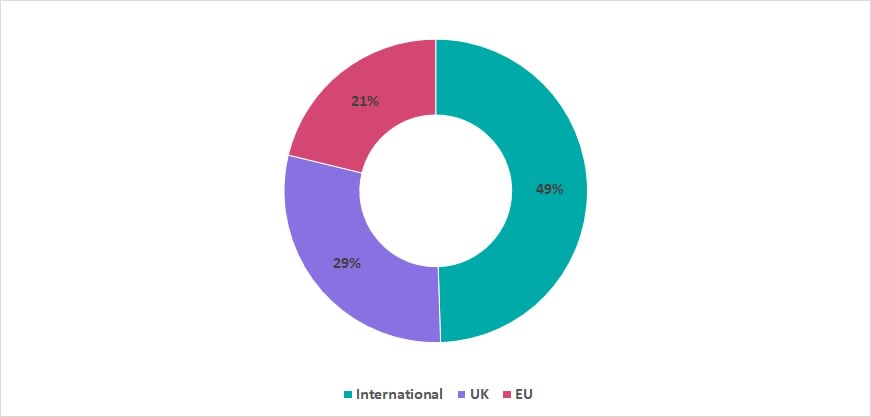

1,061 people participated in the survey, including prospective PhD students from the UK, EU and elsewhere:

1 – Survey audience

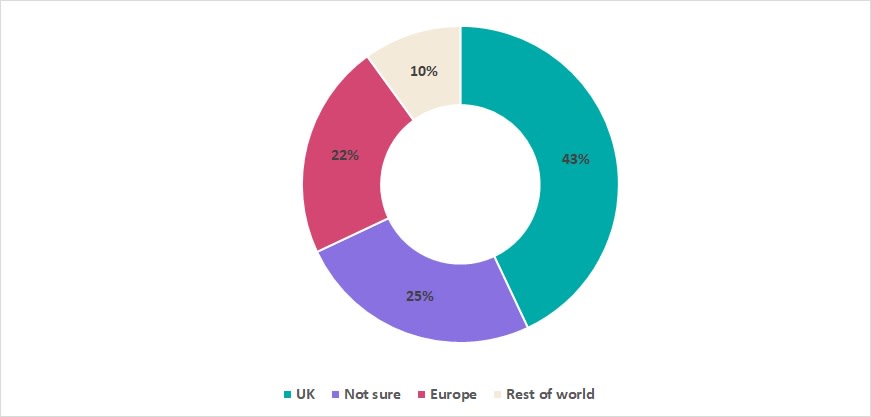

The majority of these were either seeking, or potentially considering, a PhD in the UK:

2 – Intended country of study

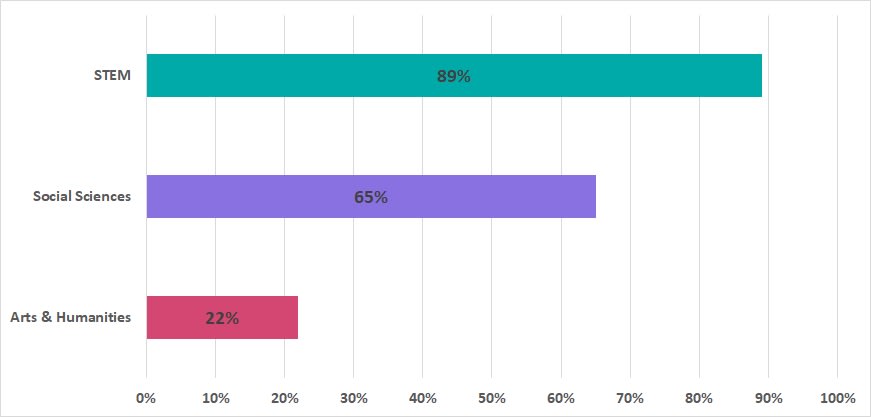

The survey also asked participants to select one or more target subject areas for their intended PhD, based on the current academic disciplines used on FindAPhD. For the purposes of this report, subjects have been grouped into broad STEM, Arts & Humanities and Social Sciences disciplines:

3 – Intended subject of study

The popularity of STEM subjects is partly reflective of the current population of postgraduate research students, 63% of whom study science subject areas.* The increased swing towards STEM in our survey may also be due to the nature of the audience for FindAPhD, which primarily lists advertised PhD research projects.

The survey also includes useful populations of potential Arts & Humanities and Social Sciences students, with 228 and 670 participants considering a PhD in these subjects.

This report will segment responses by nationality and / or intended subject area where these are relevant and / or significant to the questions and results.

*Source: Higher Education Statistics Agency, complete subject breakdown for academic year 2017/18

Several questions in the survey were designed to develop a better understanding of who the people considering a PhD are and how they plan to study.

Current activity

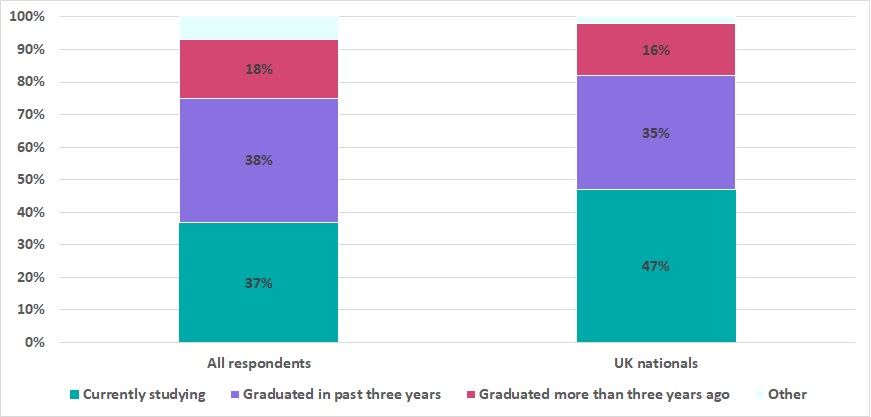

The survey suggests that a majority of people considering a PhD are not current university students:

4 – Current activity

This is less pronounced when looking at data for UK nationals, but even here, over half of prospective PhD students have already graduated from their most recent degree.

These results reveal a substantial population of prospective students beyond those currently in higher education. This audience will be missed if universities focus their recruitment on current students. Their concerns around access and funding may also be overlooked by policy makers imagining a population who are already habituated, for example, to the undergraduate application and finance systems.

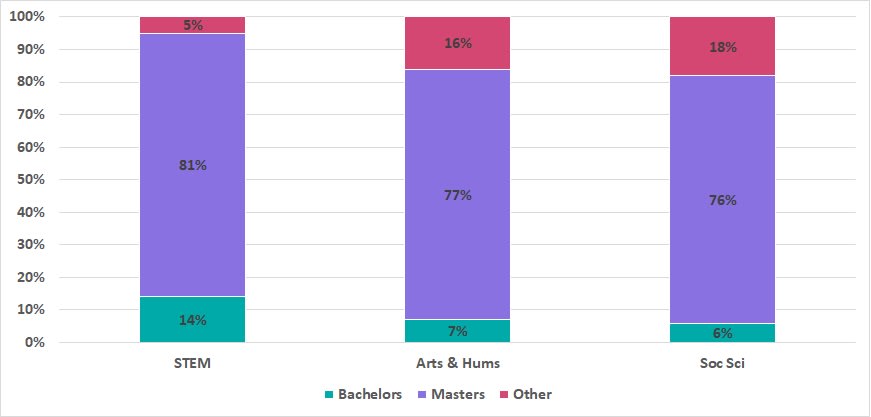

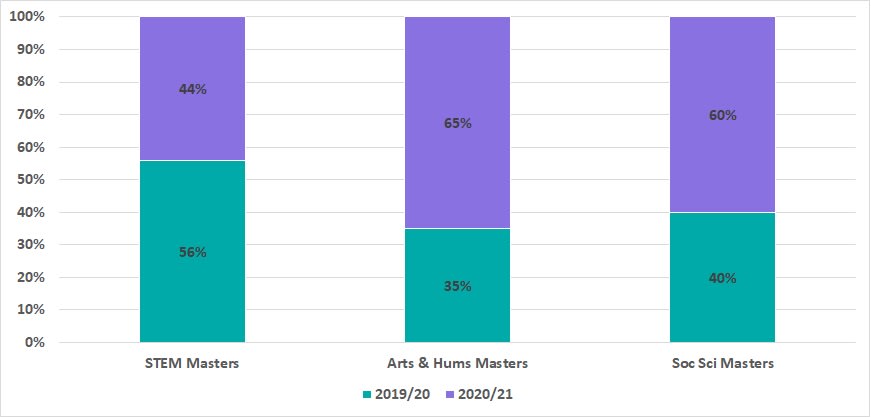

Of those who are current students, the majority are completing a Masters degree:

5 – Current study

This is potentially surprising in STEM subjects, where a Masters is less of a pre-requisite for PhD study. Arts & Humanities and Social Sciences students are more likely to be studying a Masters, however.

PhD study plans

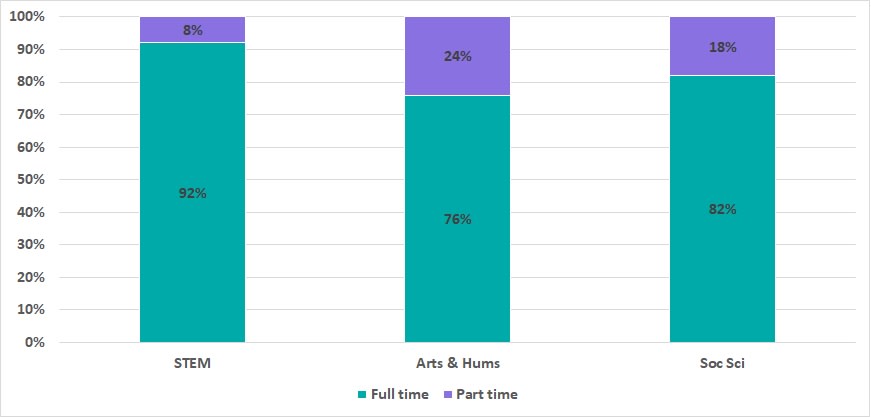

Over 85% of prospective PhD students are planning to study full-time, but exact proportions vary by subject area:

6 – Full-time vs part-time

The preference for full-time study is most pronounced for STEM students, whilst prospective Arts & Humanities students are comparatively more likely to consider a part-time PhD.

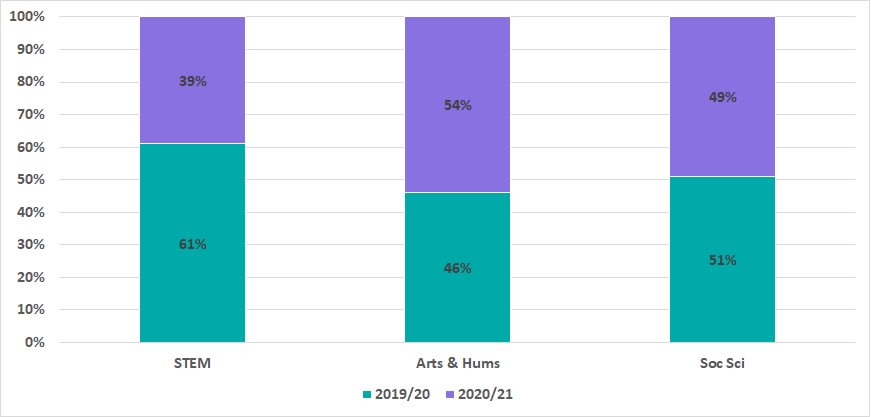

Arts & Humanities students are also more likely to plan further ahead for a PhD:

7 – Intended year of study

Interestingly, the intention to start a PhD beyond the coming academic year actually becomes more pronounced for participants who were enrolled as Masters students in June 2019 (and could therefore have progressed immediately to a PhD in 2019/20):

8 – Intended year of study (current Masters students)

This suggests that prospective students may spend more time than expected considering PhD study and seeking information about it.

Primary drivers for PhD study

The stereotypical view of the PhD positions the qualification as the route to an academic career. This clearly isn’t the case for all doctoral graduates and concerns over a supposed ‘overproduction’ and ‘oversupply ’of PhDs are occasionally raised in the media.*

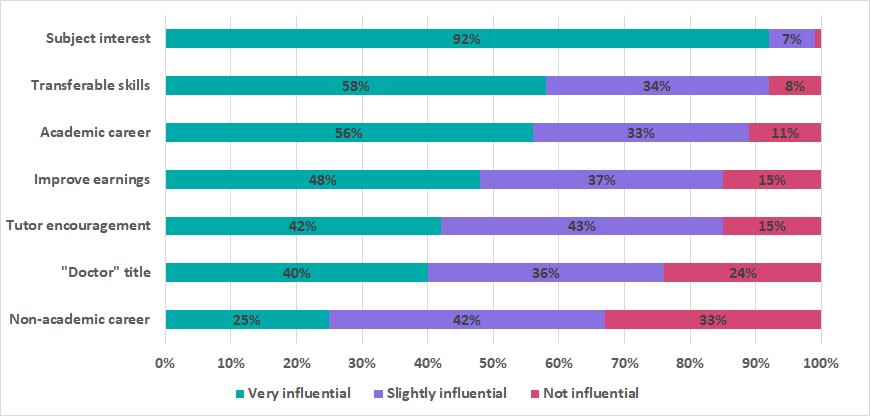

Our survey sought to investigate whether or not obtaining an academic job was actually the primary driver for considering a PhD. Participants were asked to state how influential each one of a set of given motivations was, using a three-point Likert scale:

9 – Motivations for PhD study

Interestingly – and perhaps encouragingly – the pursuit of an academic career was only the third most influential motivation, slightly behind gaining transferable skills and substantially behind subject interest. At the same time, the pursuit of a non-academic career is a ‘very influential’ motivation for a quarter of those considering a PhD.

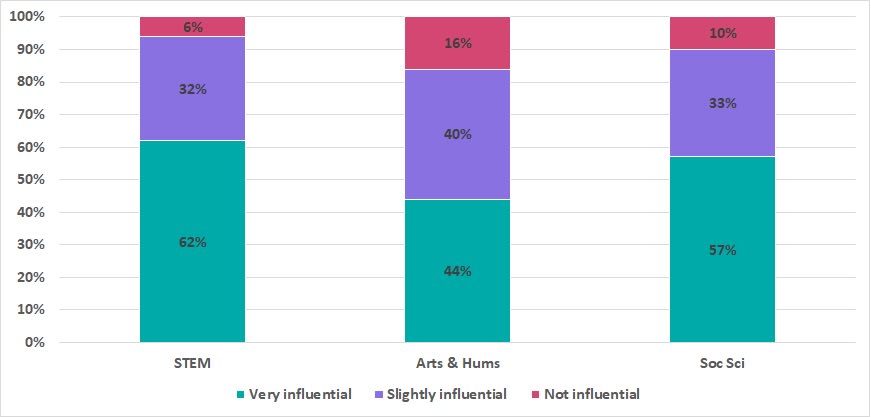

Varying motivations across subject areas

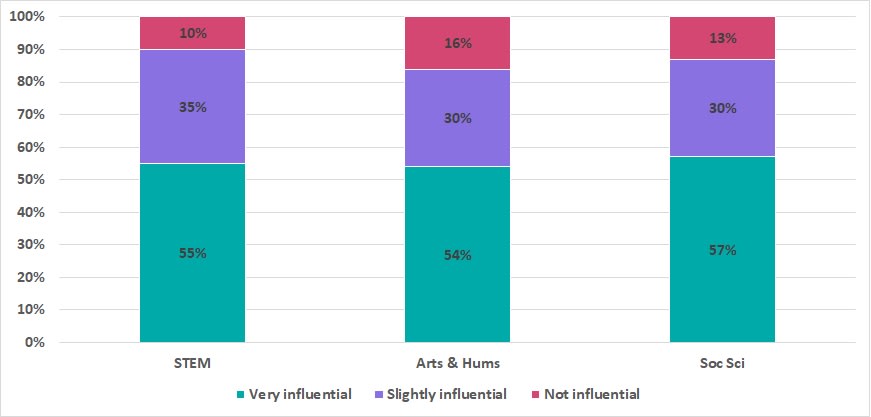

Segmenting by subject reveals broadly similar trends for the pursuit of an academic career as a motivation for PhD study:

10 – Academic career motivation

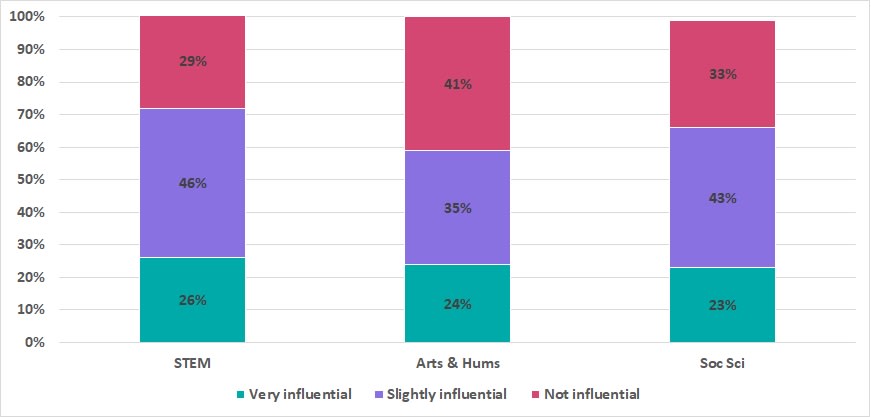

However, Arts & Humanities students are slightly less motivated to pursue a PhD as a route to a non-academic career:

11 – Non-academic career motivation

Prospective Arts & Humanities students are also the least motivated by the opportunity to acquire transferable skills, whereas this is a very influential motivation for STEM PhDs:

12 – Transferable skills motivation

Note that this does not necessarily mean Arts & Humanities students don’t regard doctoral research as an opportunity to develop transferable skills; it is simply that this is less likely to be an influential motivation for their decision to study a PhD. It may be the case that prospective Arts & Humanities students are simply less aware of the transferable skills gained through a PhD, whereas these appear more obviously defined in STEM and Social Science subjects.

Overall, it is encouraging to see that prospective students do not view the PhD solely as a route towards an academic job.

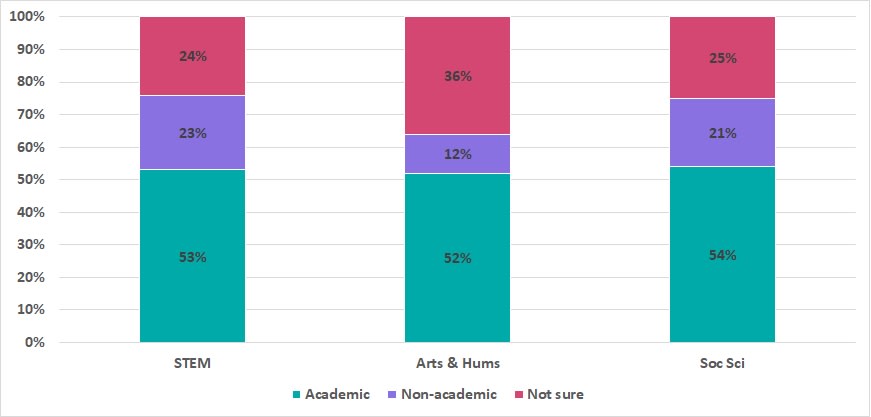

Stated career plans

As well as evaluating how influential academic and non-academic careers were as a motivation for PhD study, we also asked what prospective students actually planned to do with a doctorate.

This allows us to see where a given career path might be someone’s intended outcome without having to infer this from their motivations (or assume prospective students take a purely instrumentalist view of doctoral qualifications). Asking this second question also reveals the number of students who are unsure of their post-PhD career path:

13 – Post-PhD career plans

Across all three subject areas, the proportion of prospective students who intend to pursue an academic career is roughly comparable to the proportion for whom this outcome is a primary motivation for considering a PhD in general.

However, the proportion of prospective Arts & Humanities and Social Science students who specifically intend to pursue a non-academic career is much smaller than the proportion who give this option as a very influential motivation for considering a PhD as a whole (the percentages for STEM are roughly the same). This suggests that prospective students in these subjects may be attracted to the possibility of PhD study as a route to a non-academic career, but lack information about the options available to them.

Meanwhile, a quarter of prospective STEM and Social Science students and a third of prospective Arts & Humanities students do not know what they plan to do after a PhD. This suggests that significant numbers of people do not, in fact, view the PhD as a purely instrumental route to a specific employment outcome, but that they may seek careers guidance and mentoring during their doctorates.

PhD study differs from undergraduate and taught-postgraduate study in significant ways. We wanted to establish how well the doctoral research process was understood by those considering a PhD.

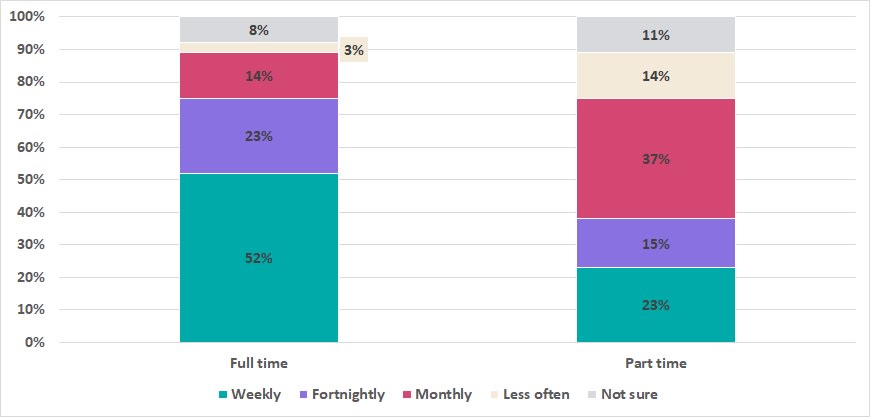

Supervision

We asked prospective students how often they expected to meet with their PhD supervisor. It makes sense to segment these responses by intended mode of study:

14 – Supervision expectations (full-time vs part-time)

The majority of prospective full-time students expect to meet with their supervisor once a week; the majority of prospective part-time students expect to do this monthly. These are probably not unrealistic, but it is worth remarking that nearly a quarter of prospective part-time students expect a weekly meeting.

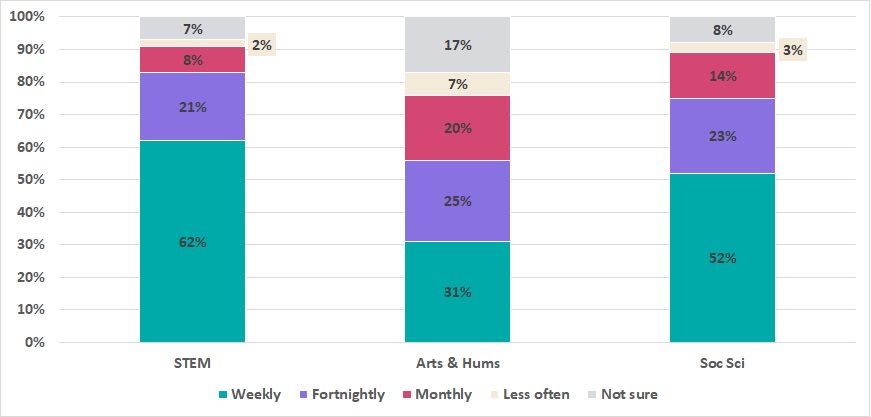

Expectations also vary by subject areas. Here we see the results for prospective full-time students segmented by discipline:

15 – Supervision expectations (by subject)

Again, these expectations appear relatively reasonable. Those who expect to be in lab-based environments or structured work groups anticipate more frequent contact with their supervisor (though they may not distinguish between routine contact and formalised meetings).

Prospective Arts & Humanities students seem to have more ambiguous expectations, with no majority option and the largest proportion selecting ‘not sure’. This may reveal a lack of clarity as to the process of independent PhD study, taking place outside a more clearly structured research environment.

Workload

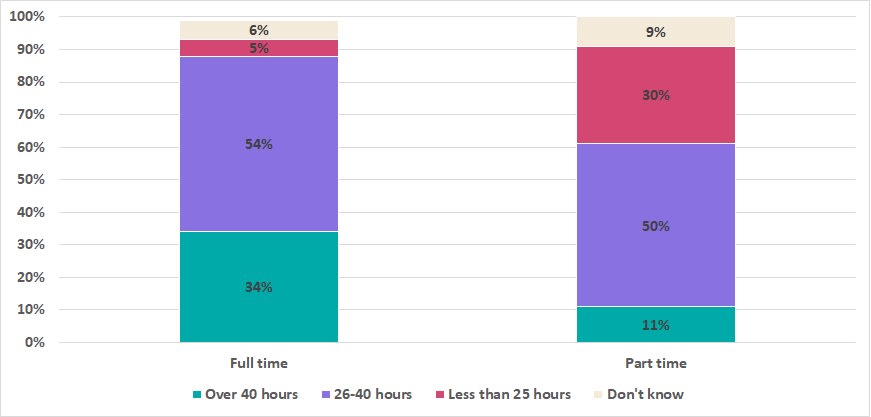

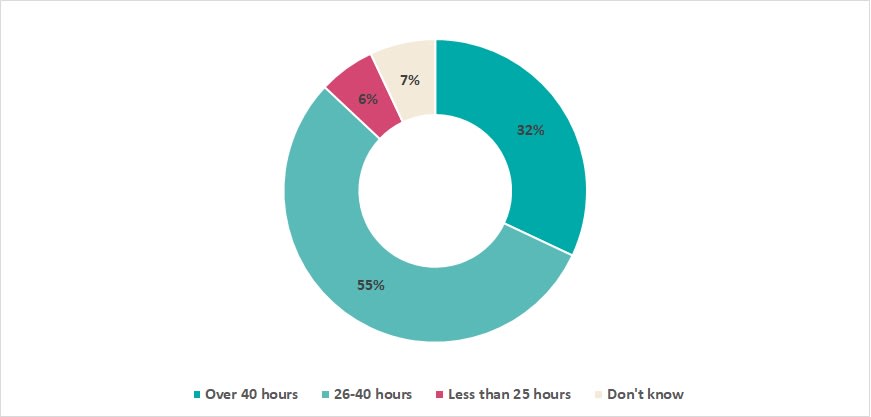

We also asked prospective students what they thought their workload would be for a PhD. Again, it makes sense to segment overall responses by full-time and part-time study intention:

16 – Expectations of weekly workload

The majority of prospective full-time PhD students expect their workload to be broadly equivalent to full-time employment, at 26-40 hours per week. However, so do 50% of prospective part-time students. Significant proportions within each segment also expect time spent on their PhD to exceed the generally recognised limits of full-time employment, with a workload greater than 40 hours per week.

What is more concerning is that the proportion of people expecting a heavy (40 hour+) weekly workload remains essentially the same for full-time students who expect to rely on paid employment as part of their PhD:

17 – Expectations of weekly workload (full-time students expecting to combine PhD study and employment)

The majority of students who expect to rely on paid work to fund their PhD are also prepared to commit to a full-time workload (or more) for the doctorate itself.

Increasing attention is being paid to the relatively high incidence of mental health problems amongst PhD students, with suggestions that these are partly linked to overwork. It seems clear, based on the responses above, that people considering a PhD do anticipate a heavy workload, though this may not necessarily prepare them for it.

We consider prospective students’ own perceptions of the PhD’s impact on mental health and wellbeing later in this report.

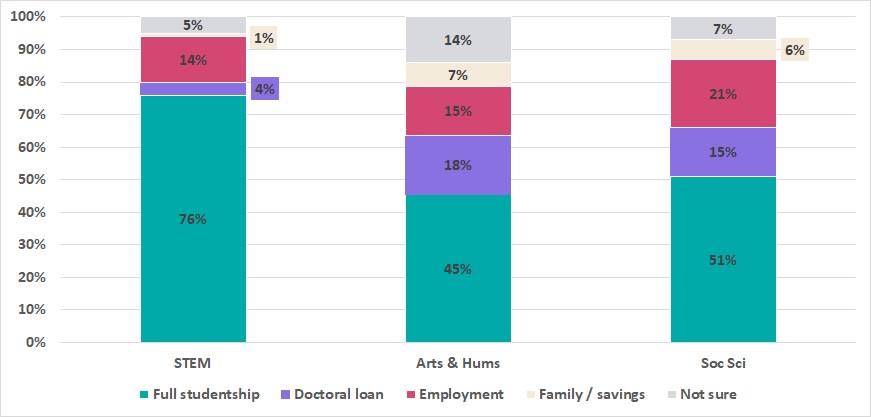

The funding of PhD research in the UK has been dramatically altered by the introduction of doctoral student loans in the 2018/19 academic year. For the first time, most UK students have a statutory right to some financial support for doctoral study. This represents a shift, in principle and in practice, from a system where the main form of government funding for PhD research was offered through competitively awarded UKRI studentships.

The prospective students responding to our survey in June 2019 had the opportunity to join the second cohort for whom this funding would be available. We asked them how they expected to fund their PhD.

Primary funding source

We asked prospective students to pick one of a range of options as the primary funding source for their PhD:

18 – Primary funding expectation

The data here is segmented to UK and EU students as these would be eligible for both UKRI studentships and doctoral loans.

The relative proportion of prospective students relying on a full studentship makes sense and reflects generally held assumptions about funding methods across disciplines. Arts & Humanities and Social Sciences students may be able to fund a PhD through combining multiple forms of support (including work and savings) whereas the expectation for STEM is that most students will be accepted to fully funded projects.

Notwithstanding this, it is perhaps concerning to see that roughly 15-20% of prospective students expect to use paid employment as their primary source of PhD funding. This supports the earlier impression that PhD students may be anticipating and accepting very high workloads.

Doctoral loans

The doctoral loan provides a maximum of £25,700 for a PhD beginning in the 2019/20 academic year.* This may explain why a limited number of prospective students expect to use this as their primary funding option; those that do presumably intend to supplement the loan with paid work, partial scholarships or other financial resources.

We asked a selection of other questions to assess how the people seeking a PhD perceived this new funding option. All responses are segmented to UK and EU students who would potentially be eligible for the doctoral loan.

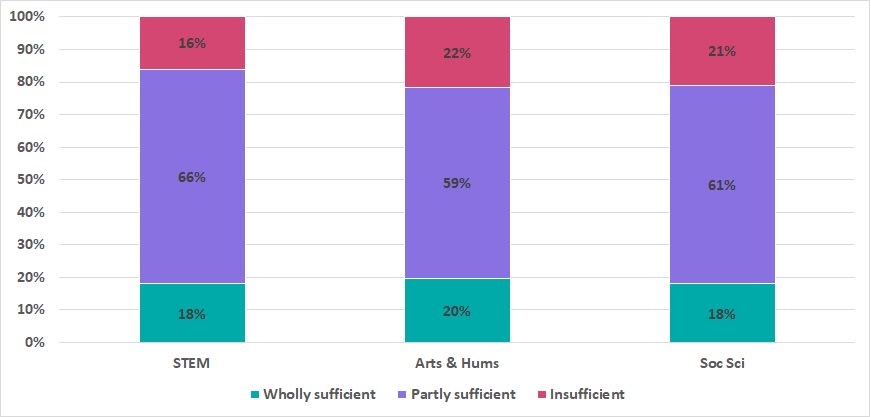

We first asked whether prospective students thought the doctoral loan amount was sufficient:

19 – Doctoral loan value

In responding to this question, participants agreed with one of three statements:

- That the loan was wholly sufficient: "It will make PhD study affordable for me without needing additional funding"

- That the loan was partially sufficient: "It will make PhD study affordable for me if I can find additional funding"

- That the loan was insufficient: "It won’t make a PhD affordable for me, even with additional funding"

Most prospective PhD students recognise that the doctoral loan offers a partial funding option and that its value is sufficient for this purpose. Very few regard the loan as sufficient to fund a PhD, in isolation. This suggests that a high proportion of prospective PhD students do have some awareness of the cost of doctoral study.

There is very little variation in responses by subject area. Interestingly though, people considering an Arts & Humanities or Social Science PhD are more likely to regard the loan value as completely insufficient.

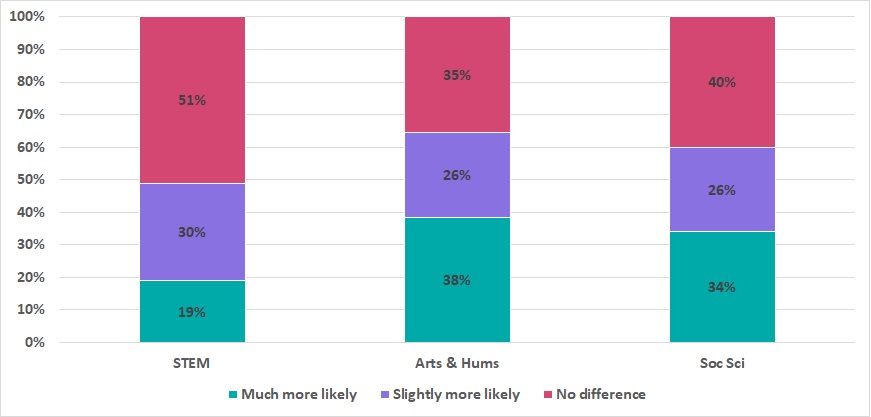

Part of the intention behind the launch of the doctoral student loan was to increase participation in PhD-level study.** To that end, we asked prospective students how much of an impact the availability of the loan had made to their decision to study a PhD:

20 – Doctoral loan impact

Relatively little impact is visible for STEM subjects. This makes sense if these students are assumed to seek out (and require) fully-funded projects. However, this raises questions about the loans’ ability to widen participation in PhD study across all disciplines.

*The maximum value of the doctoral loan has since risen to £26,445 for 2020/21 starters

**The PhD loans were initially announced in the 2015 Budget (PDF), which promised to "broaden and strenthen support for postgraduate researchers" and respond to a situation in which "UK PhD enrolment has remained relatively flat" relative to other higher education systems. The 2016 Budget (PDF) then situated the loans as part of a broader investment in "lifetime learning".

The unique nature of a PhD means that students require more detailed – and nuanced – information and guidance resources, such as those provided on FindAPhD and other specialist platforms. The information universities present about themselves for student recruitment purposes also needs to fit the needs of this audience.

We therefore set out to discover what information prospective PhD students prioritise, how they seek it and how easily they find it.

Information seeking

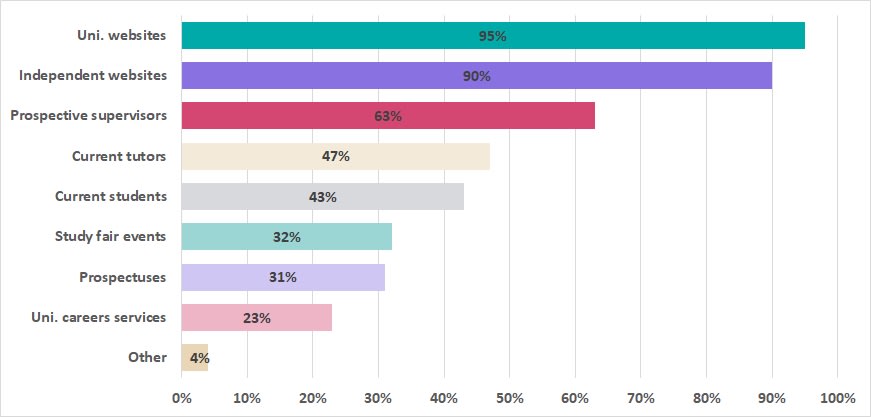

We asked prospective students to tell us which resources and channels they used when looking for information about PhD study.

Participants could select multiple options that they had used or planned to use during their PhD search.

The results for UK students were as follows:

21 – Information seeking (UK students)

Web resources, including university sites as well as independent resources such as FindAPhD were by far the most popular platform for PhD information seeking. After these, prospective students are most likely to seek information from prospective and current supervisors, or from current PhD students.

Nearly a third of UK students would also attend a PhD study fair event – marginally more than would consult a prospectus.

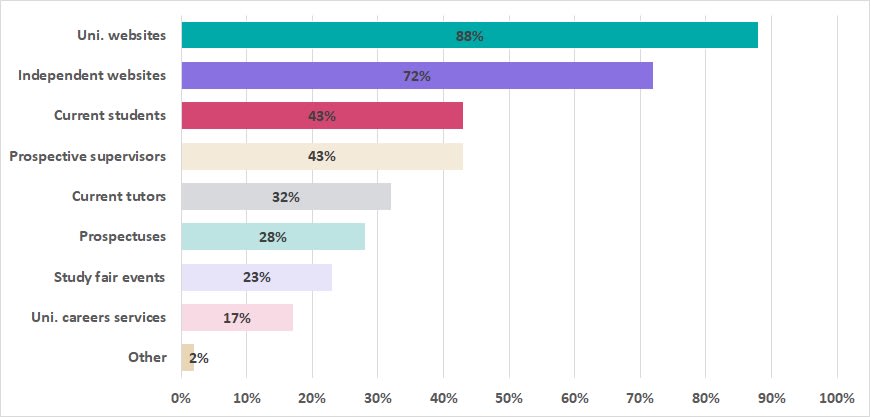

The results look slightly different for EU and international students:

22 – Information seeking (non-UK students)

Websites remain a significant source of information, whilst current students become the most important source of ‘one-to-one’ information. Those considering studying abroad are also understandably less likely to attend a physical study fair event.

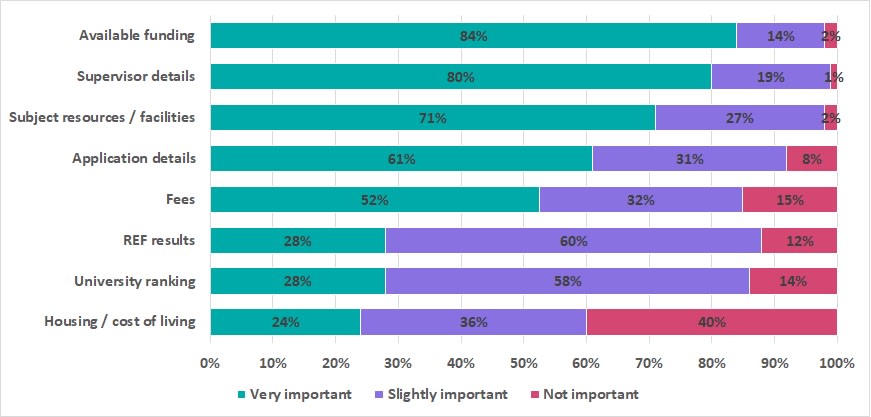

Information priorities

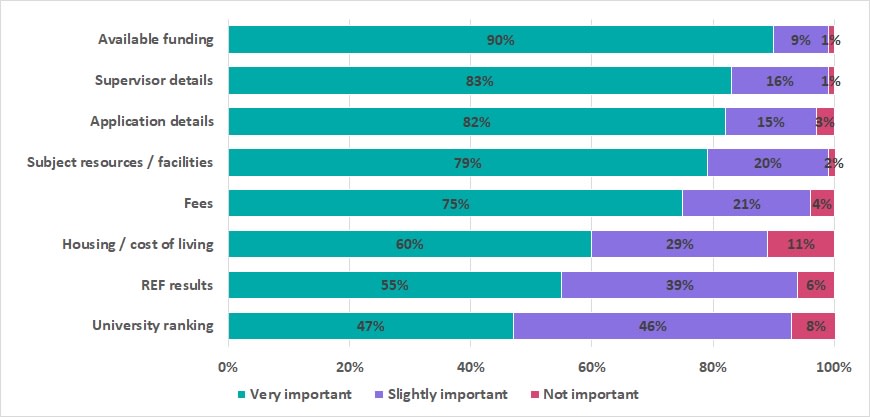

We also asked prospective students to tell us how important certain types of information were when considering universities for PhD study:

23 – Information priorities (UK students)

These results are broadly similar when segmenting by discipline, though prospective Arts & Humanities PhD students are slightly more focussed on supervisor details (with 88% agreeing that this information is ‘very important’); this makes sense for subjects that are most defined by a traditional ‘mentor-mentee’ supervision process, where the interests and experience of the supervisor will determine the viability of a student’s PhD proposal.

Results are broadly similar for international and EU students, who are more likely to be looking for a PhD abroad:

24 – Information priorities (non-UK students)

Of note is the fact that prospective non-UK students place ascribe more significance to quantitative metrics such as a university’s REF result or its ranking in comparative league tables. These are ‘very important’ for around half of non-UK students, vs roughly a third of UK students.

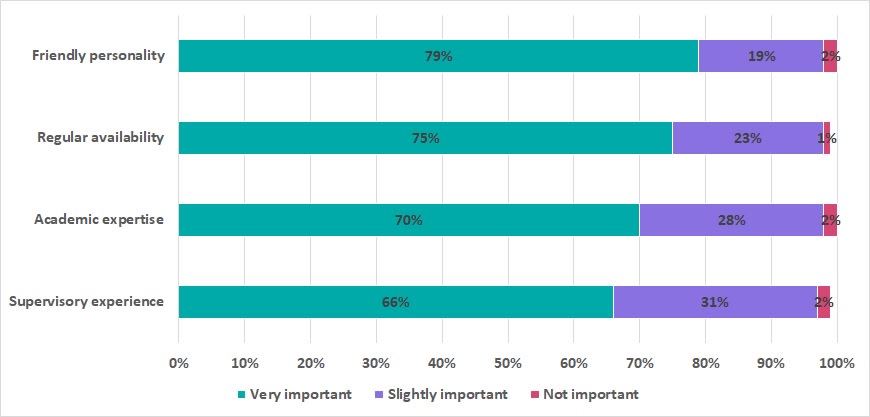

Supervisor qualities

The majority of prospective students prioritise information about potential PhD supervisors. We also asked them to rate the different qualities they might be looking for:

25 – Supervisor qualities

Interestingly, the most ‘quantifiable’ qualities of a supervisor – their academic profile and experience of supervision – were the least likely to be rated as ‘very important’. Instead students prioritised qualitative aspects such as the supervisor’s personality and availability.

All four of these criteria were regarded as ‘very important’ by the majority of participants, but universities may find that information on supervisors’ personal background, interests and supervisory practice resonates best with prospective PhD students.

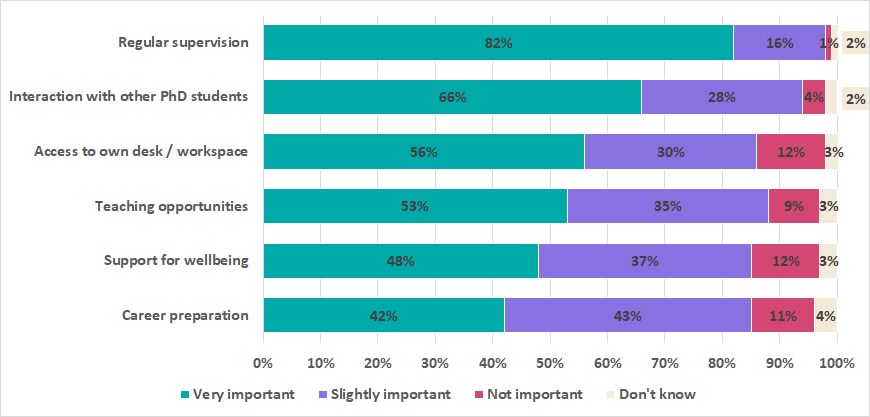

Qualities of the research environment

As with supervision, we asked prospective PhD students to rate different aspects of the research environment at the universities they might consider:

26 – Research environment

Again, supervision is a key factor in students’ decision-making, but the second-most important feature of a university research environment is the ability to interact with other PhD students, which 66% describe as ‘very important’. This affirms the value of cohort-based approaches to doctoral programme design, but also suggests that prospective students may appreciate recruitment messaging that showcases the wider postgraduate research community within a university department.

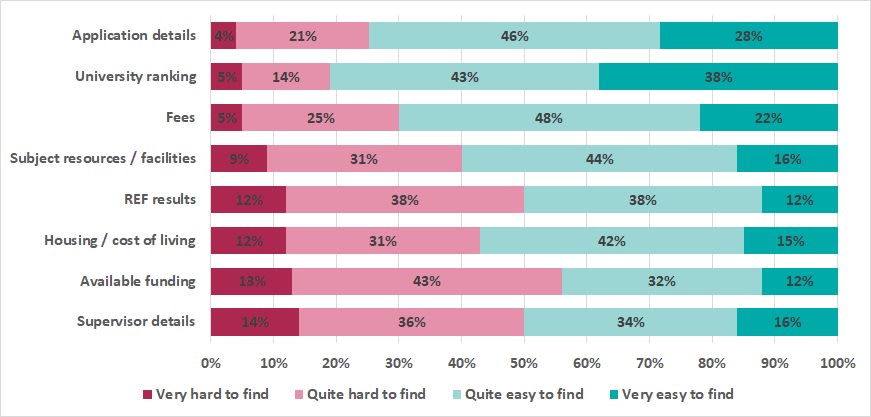

Information availability

Having explored the way prospective students prioritise information about PhD study and the channels they use to seek it, we also asked how easy or difficult the process of acquiring this information was:

27 – Availability of information

50% or more of prospective PhD students have difficulty finding details of supervisors or funding opportunities: the pieces of information they prioritise most when considering universities. Information on resources and facilities for their subject is also relatively hard to find.

Conversely, relatively few prospective students have difficulty finding information about universities’ PhD fees and application process.

A key part our survey’s value comes from the unique insight it offers into the experiences and activities of people seeking a PhD, as opposed to those who are already completing one. By definition, this means that our participants include some people who may not go on to study for a PhD.

We wanted to examine the potential factors behind this by asking what concerns prospective students have about PhD study.

Students’ concerns

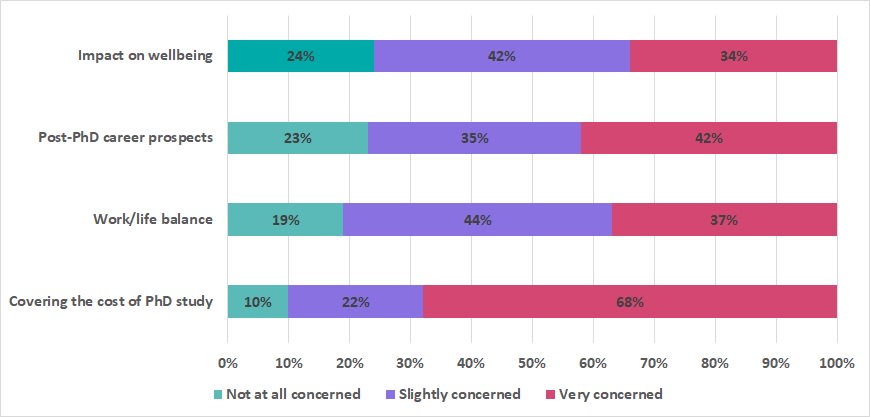

We asked participants to state how concerned they were about four different aspects of PhD study:

28 – Barriers and concerns

The financial impact of studying for a PhD is a significant concern for the majority of students. This in turn may explain why a third are also ‘very concerned’ about the impact of a PhD on their work life balance.

Our survey has already revealed that prospective PhD students anticipate a heavy workload and that many still expect to take on additional paid employment. We can now see that they are concerned about this, but presumably see it as necessary to finance and complete a PhD.

Associated with this, the impact of a PhD on personal wellbeing is also a concern for more than three quarters of prospective students. Again, this suggests a pre-existing awareness of these issues for people considering a PhD.

Finally, more than three quarters of prospective students are also concerned about their career prospects with a PhD. This is despite the majority having an academic or non-academic career in mind prior to commencing a doctorate.

Taken together, these results suggest that widely publicised concerns about PhD workload, the academic jobs market and the impact of a doctorate on mental health are shared by prospective students to whom these messages may also be filtering through.

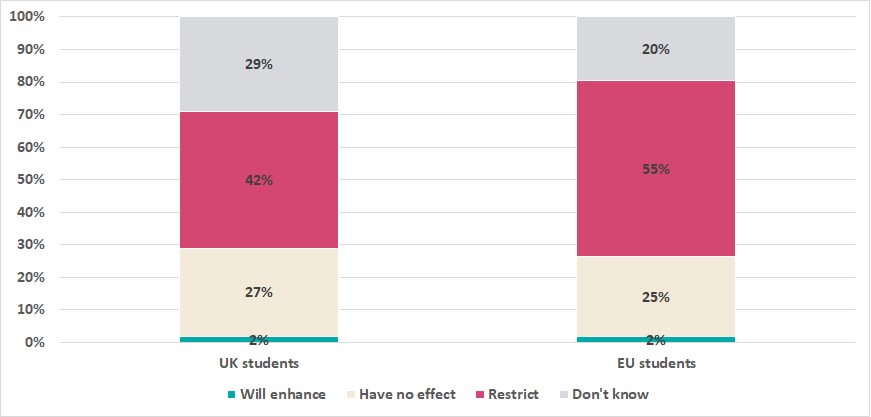

Brexit

The exact impact of Brexit on PhD study in the UK remains to be seen. Fee and funding guarantees are in place for EU students commencing a PhD at UK universities in the 2020/21 academic year, but the future extension of these is far from certain. Meanwhile, the prospects for UK students considering a PhD in one of the 27 other EU member states are unclear, with varying policies and levels of information.

We asked students what effect they expected Brexit to have on their PhD opportunities:

29 – Perceptions of Brexit

EU students are more likely to expect a negative impact from Brexit, despite being aware of fee and funding guarantees.* UK students are also slightly more unsure of the impact. This may be due to a greater perception of Brexit uncertainty in the UK and / or to the fact that less information is available on the future terms for UK students in Europe.

*Our survey point was June 2019 and the statement on Brexit was therefore phrased as follows: “Brexit is due to take place in 2019, though current fee and funding regulations will continue to apply for EU students starting degrees at UK universities in the 2019/20 and 2020/21 academic years.”

This survey provides a range of new information on how and why prospective students approach PhD study. This report has provided a summary of the findings, but certain key conclusions and takeaways may be worth considering for those involved in policy making, programme design and student recruitment for doctoral degrees.

Our survey results reveal the following:

- Prospective PhD students are not necessarily current students – More than 50% of the people seeking a PhD have already graduated from their most recent prior degree. As a result, they may not be reached by marketing and recruitment that primarily targets current Bachelors and Masters students.

- People invest substantial time in considering and choosing a PhD – 39% of STEM students, 54% of Arts & Humanities students and 49% of Social Sciences students say they aim to begin a PhD beyond the coming academic year (when surveyed in June). These proportions increase for students who are currently completing a Masters.

- Prospective PhD students are not exclusively motivated by the prospect of an academic career – Whilst qualifying for an academic career is a ‘very influential’ motivation for 56% of students, more than 50% are at least partly motivated by the prospect of a non-academic career; however, a much smaller proportion specifically intend to pursue such a route after their PhD.

- Prospective students may value inter-personal and qualitative aspects of a PhD experience over quantitative metrics – The availability of friendly and accessible supervisors and opportunities to interact with other PhD students are more highly rated than academics’ professional achievements or universities’ rankings. Student recruitment and university IAG resources that focus on these areas may be more useful and resonant for students.

- Doctoral loans may have a limited impact in certain subjects – Prospective students generally regard the UK doctoral loan amount as partially sufficient to support PhD study, but more than 50% of STEM students feel this new funding will make no difference to their decision to pursue a PhD. The doctoral loan may not widen participation and improve access across all subject areas, therefore.

- Students anticipate the potential negative impacts of PhD study, but could be proceeding regardless – 89% of prospective full-time students and 61% of prospective part-time students expect the workload for a PhD to be equivalent to or greater than that for full-time employment. Regardless, 82% are also concerned about their work/life balance during a PhD and 76% are concerned about the potential impact on their wellbeing.

We invite feedback on the results presented in this report, including requests for more information (where available).

An expanded edition of the Future PhD Student Survey will run in 2020. To be notified of the launch or to suggest modifications, please contact [email protected]